Interview with Tim Etchells

while preparing for EVI LICHTUNGEN in Hildesheim 22–25 JAN 2026.

INTERVIEW BY Khadouja Tamzini

PUBLISHED 6 JAN 2026

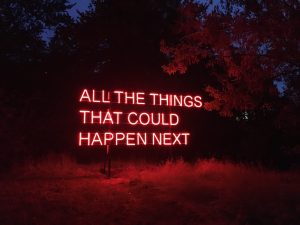

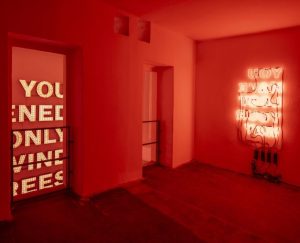

In the EVI LICHTUNGEN 2026 edition, Tim Etchells is participating with his installation “Never Sleep” on the façade of the Amt für regionale Landesentwicklung Leine-Weser. Please meet Tim Etchells, who answered Khadouja Tamzini’s questions.

// You have worked with neon and LED signs for over twenty years. What does light allow you to do that other media do not?

There’s certainly something in the charm, alure and urgency of the illuminated phrase that I’m drawn to. The way that language in that form seems to have a kind of doubled presence. I guess I’m thinking in “pure” terms about the extra go-faster zip that light gives to something, but also in relation to the other (capitalist or functional) urgencies we might associate with signage and advertising. The work in that sense draws on a set of vernacular urban practices as well as artistic ones. Working with light has become one of the main ways for me to work in public space – the possibility to float questions or poetic assertions or nonsensical imperatives into landscape or cityscape continues interest and excite me.

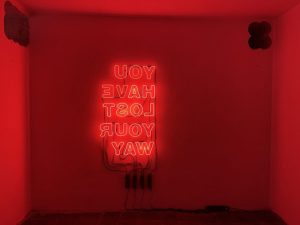

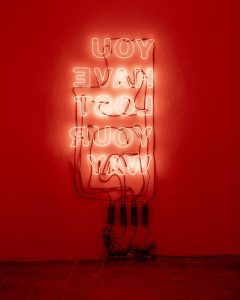

// Your work consistently treats language not only as a vehicle for meaning but as a material in itself. What first drew you to using short, direct phrases as sculptural and spatial interventions?

I’ve always been obsessed with linguistic fragments. The phrase that one remembers from a movie, the fragment of conversation one overhears on the bus, the three words you underline in a book. My brain seems tuned to that and to the way that fragments demand or invite imaginative completion. As a consequence, my notebook is filled with such material.

I guess I’ve been working my whole life with that… and with finding ways to explore that ambiguous, contradictory space. Working with neon (and with LED) came at a certain moment… but I’ve also explored “the fragment” in performance, in sound installation, in musical collaboration, in drawing, in video installation…

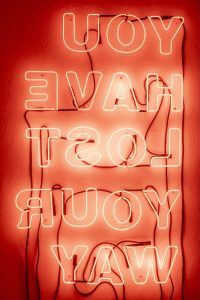

Specifically, in terms of neon, I like the way that these phrases demand to be read and re-read. It’s language as object. The situation around the object changes… the city changes, the people change, the social context changes, the perceiving subject changes… and the work in a sense “stays the same”… insists on itself, on its visual presence, its semantics. But of course, the changes in all those other contextual things change the work too, reveal it in new ways, open new perspectives on it. This dynamic tension between the work as a fixed thing and the field of uncertainty that surrounds it, emanates from it is what I’m drawn to.

// Neon signage is often associated with commerce, advertising, and nightlife. How do you play with or subvert these associations in your artistic practice?

I guess some of the allure I was mentioning is related to this. Neon (in modernist cityscape, in the capitalist mythological at least) is some index of desire, some glow of unnamed promise – a shorthand for sex, adventure, the city. While the city (and capital) has moved on, neon retains some of the properties above, a faint charge, a cliché that is still resonating. I like working in that ruined semantic and aesthetic territory, but as much as the work leans on or plays with that allure, I also try to subvert it. Many of the works use language fragments that are both comical and, in a certain sense, disturbing. They’re also very often impossible to “resolve”. Advertising (usually) I would say has an end goal,.. even if it makes use of ambiguity or semantic confusions there’s a rather utilitarian bottom line (sales/brand development). I like my work in public space (neons, posters, billboards, etc.) partly because it refuses this sales function and instead draws the viewer into spirals, more complex interior and social territory.

// “Never Sleep” is a short, direct phrase, yet it carries multiple possible meanings. How did this work originate, and what first drew you to this particular sentence?

I don’t honestly remember. It’s in my notebook…. But I am not sure how it got there. I can say it’s one of the works that deals with this idea of a kind of impossible and impossibly urgent imperative. Encountering it, we appear to be being addressed directly and commanded or “strongly advised” by means of these two words.

I enjoy it as a call to vigilance – to not relaxing, to not taking one’s eye off the ball, to keeping watch, to some continuous attempt to keep track. But at the same time, of course, the imperative it announces is also immediately and obviously impossible. Staying awake forever insists on being alive and active in the world continuously, without a break… but we all know that’s not possible. The work proposes an act of self-destruction. I guess another genre of work that I’m interested in is that of “bad advice”… the voice of the work can’t be trusted…

// “Never Sleep” has been shown in multiple locations in Hildesheim since 2018. How does the meaning of the work shift for you when it is placed on different buildings or within different institutional and urban contexts?

It’s an interest for me that these “fixed” works, pieces of semantic communication via language, are also fluid, shifting, changeable – “porous to context” is the phrase I tend to use. Wherever you put them, and whenever you put them, they are different works. The work is one thing, and its dialogue with the context (spatial, social, political, temporal) is another…

// You frequently refer to your interest in rules and systems in language and culture. In works like “Never Sleep”, where do you see the balance between control (the fixed phrase) and openness (interpretation)?

In general terms, I think about the works offering a very particular, precise, and vivid set of cues, references, or coordinates. There’s a strong offer in which certain quite particular ideas, tensions, and images are floated. But when we look closer there’s also a lot of air in between and around the vivid proposition of the work; questions that are raised but not answered, narratives are invoked but not completed. The ambiguity they create is an active state. Never Sleep…. sure… but why not sleep? There’s an imperative, but we are left to speculate about the reason or reasons. … and really “never”? Where would that leave us?

// Much of your work concerns presence and events unfolding in time. How does a static phrase like “Never Sleep” continue to “perform” over time in a public setting?

I do find it interesting that the public space pieces are visible in the same location over a period of weeks, months or years. It means that people living in proximity or visiting a place repeatedly can get to see and re-see the pieces, in different circumstances, at different times of day or in different seasons and weather conditions, in different personal circumstances, in relation to different social or political events. Again, I’m drawn to this idea that the work remains static in one sense but that changes in context or circumstance draw out new inflections of the work. So, I think the passage of time helps deepen the experience of the work, adding layers and perhaps tuning the viewer to the contingent or dialogical nature of their meaning.

// Many of your neon and LED works initially place the audience in a moment of uncertainty or incomprehension. Why is this moment important to you, and what do you hope it opens up for the audience?

I see the works as opening a space rather than making a statement. There’s a conscious attempt to create something that can’t quite be resolved – the combination of a strong offer, but dynamic tension and unanswered questions that I spoke about before is really key.

// Do you see the audience as completing the work through interpretation? Has a public reaction or misreading of one of your text works ever significantly changed how you think about it?

I do see the audience as completing the work. The work is a catalyst, a provocation, a way of setting a process in motion. But I don’t really see the audience role as one of interpretation – that would seem to imply that they are tasked with figuring out or reading the work. I see the role much more as activating the work, embarking on a process in relation to it or alongside it. The work resists reading or interpretation in fact. It doesn’t ask to be “read” – instead (at best) I think it begins a process that has no end; tensions, questions, contradictions are activated, and that space of uncertainty between them and around the work persists in the viewer.

Sometimes people do come up with very specific readings or responses, of course. They’re not wrong; I don’t feel like they are misreadings. But for me, a single reading is always less interesting than the tension between the multiple meanings that the work’s permission actively cultivates. A singular reading in that sense is a narrowing. I’m interested in resisting that.

One of the works (“Let’s Pretend This Never Happened”) was installed for a while on the façade of the National Theatre in Lisbon. I had an email from someone who said that a tour guide had told them that the work referenced the burning of witches on the site of the building in 1600 or something. They wanted to know if that reading was correct. I said it’s correct, in the sense that that is the connection that someone has made… but that I wasn’t aware of that history. Putting the work in that location activates that possibility, that potential meaning… regardless of any intention of mine. The meaning/s of the work, it’s resonances and so on, do not belong to me or need permission from me.

That said, though, it’s important to me that a “reading” like this – this kind of specific link or connection to a narrative – should not sideline the other possible meanings, narratives, questions, or ideas that arise from and around a work. A general problem perhaps with art education at a certain level (or broad cultural/social attitudes to art) is that they encourage the idea that there is a meaning in art work that needs to be found, identified, fixed or named and that once this process has been completed the work, having been “seen” or “read correctly”, can be put aside, reduced effectively to its message. In my experience, actual artwork resists this profoundly. It can’t be resolved. I am listening to The Falls’ “Hex Enduction Hour” or Keith Jarrett’s “The Koln Concert”, looking at the Richter abstracts from 1989, or reading Kathy Acker for more than 40 years, and I still don’t know what they mean or what they are saying to me. I know (some of) the energies that circulate in them, (some of) the thoughts that they awake… but this dynamic work is never finished. There is no interpretation as closure, only continuous encounter. Anything less than that misses the point.

// Your artworks often appear in unexpected locations: façades, rooftops, street corners. How important is the element of surprise in encountering your work?

A lack of context can be useful. Often, the neon works in public space cultivate this vividness, this urgency I have been speaking about, but do not announce their position – who is “saying” this? On what authority or with what purpose is this statement or phrase present in the city? Since these things are often unknown the ambiguity around the work is multiplied and that can be very useful to me. The works are in the city to some extent without a frame… and I do think that can be part of their potency.

I’m also aware that this all hits different audience members differently – some people go looking for the work as part of their engagement with a particular programme or institutional offer, other people will chance upon it without knowing the context. Both are fine and clearly open different approaches to the work itself.

// Your practice often reflects on contemporary urban life and identity. What does the city offer you as a site for artistic intervention that a gallery space cannot?

I think the fact that the work can be in a direct relation/dialogue/counterpoint with the lived reality of urban space is important to me. The works speak to viewers, but they also interact dynamically with history, with current and past usage of the city, with other aspects of the built environment, and with urban vernacular. By contrast the “white cube” gallery appears a little more sheltered/removed from those realities – there are less other forces immediately and dynamically present (although of course gallery space also has history, cultures of use and frames of expectation with which one can engage).

// You’ve described your public text works as creating moments that are “public but private at the same time”. How do you think intimacy can exist in public space, especially in cities saturated with images and messages?

The works in the city stage a very public dialogue and engage with the urban context on its own terms, and one can think about them in that way. But I’m also mindful that individuals are busy with their own stories, their own thoughts, their own associations. The work with text fragments can offer a kind of two-way gaze… we can look outwards, to the city, the context, the historical frame, the social and political frame, and we can look, at the same time, to more private questions and resonances. “Let’s Pretend None of this Ever Happened” can be about the historical narratives of the site, the immediate context of the city and its politics… but it can also be about the viewer’s personal narrative – the divorce they are going through, the tense situation with a sibling or a child, or with some truly granular personal experience. The scale and direction of the gaze with a work like this is not indicated… so an intimate reading is always possible.

I guess one of the things I’m used to is the idea that viewers/spectators all construct their own relations to artworks, performances, texts. I actively enjoy the way that different people will take their dialogue with the work/s in different directions.

// This year, the work is presented on the façade of the Amt für regionale Landesentwicklung Leine-Weser. What role does the surrounding institution play in shaping the meaning of the piece?

Install context brings new information into the frame… new narratives, new layers of possible meaning. The work changes wherever one puts it. Part of my desire in making neon from a phrase… or drawing a phrase… or making a phrase out of letters made of ice… is to find out what the language might mean… shifting locations is another way to trick new possibilities from the material. Another way of opening the work in different directions, opening it to other understandings.