Interview with Gudrun Barenbrock

while preparing for EVI LICHTUNGEN in Hildesheim 22–25 JAN 2026.

INTERVIEW BY Anna Muni

PUBLISHED 16 JAN 2026

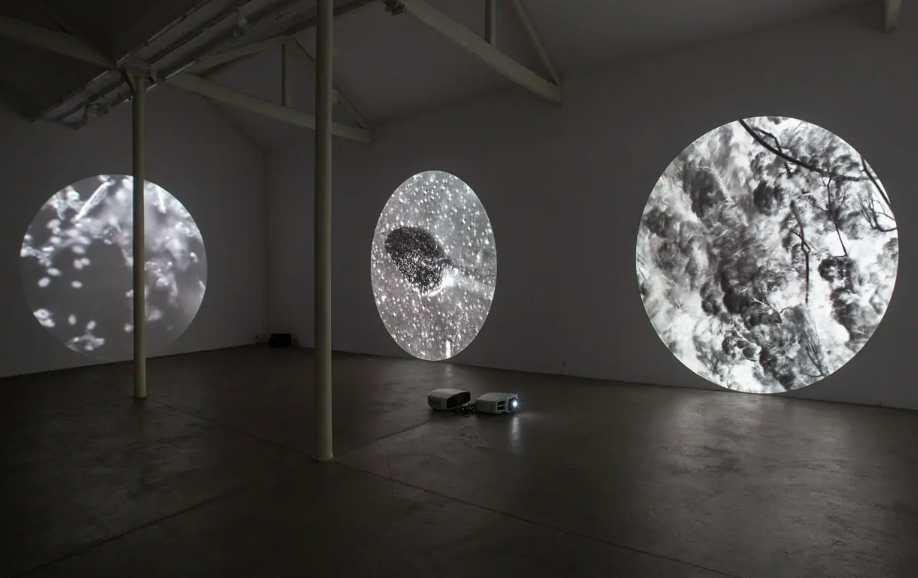

Gudrun Barenbrock is a video artist who creates immersive visual spaces using film and photography, placed within architectural settings. Her minimalist works, often in collaboration with sound artists, oscillate between figuration and abstraction, forming dynamic, sensual landscapes that transform the space.

In the EVI LICHTUNGEN 2026 edition, Gudrun Barenbrock presents her video montage “Zwischen Räumen (Mapping the City)”. The work combines photo and film material from everyday urban observations, including satellite and drone imagery, views of architecture, landscapes, traffic routes, and footage from Hildesheim. Digitally reduced to minimalist black-and-white contrasts, the material is edited into rhythmic animated sequences. Projected onto the façade of the Kolleggebäude Mariano-Josephinum, the work transforms the functional school building and its surrounding car park into an experienceable in-between space. Barenbrock’s intervention turns the projection into a stream of consciousness, revealing hidden dimensions of urban life and stimulating imagination and association.

// Can you describe what initially led you from fine arts into working with video installations and projection mapping, and why the camera became your primary tool?

First of all, mapping is not my main focus—I make films, so there’s a difference. This time I’m doing a mapping for this project, but it’s an exception, so please keep that in mind. I don’t see myself as a mapping artist. What’s important is that with my videos, I aim to create special spaces. I personally prefer indoor settings. Of course, I’m glad to have the opportunity to show something in Hildesheim, but if I could choose, I would always prefer an interior space. It gives more possibilities to create a space with light. You don’t just have the walls—you have the floor and the ceiling too. You can create a surrounding space of light, which is much more interesting both for me as an artist and, I think, for the audience. Outdoors, when projecting on a façade, it’s always a bit like an open-air cinema—it feels flat. That’s why, for Hildesheim, I asked to work with two sides of the building, not just one. The projection wraps around the corner, adding a three-dimensional aspect—a band of light moving around the building.

So why do I work with light? When I was at art school, I studied painting. My paintings were always quite large—not just small pieces to hang on a wall. Even then, I was already trying to create spaces through painting. But as the spaces got bigger, it became really difficult—so much work, and physically demanding to move everything. That’s when I started experimenting with light, initially with small projections. Light allowed me to enlarge an image without having to carry heavy materials or rent trucks to transport oversized works. At that time, I didn’t have the money for large-scale paintings anyway—like most students just out of art school. Light gave me the chance to create temporary works anywhere. Once I unplugged the projection, it was gone—I only needed a small bag with my slides. From there, it felt natural to move from static images to moving images. As soon as I could afford a used camera—a Sony—I started exploring film. I was absolutely fascinated by the new possibilities this tool opened for my artistic work.

// Your unique artistic approach, combining cinematic and photographic materials, architecture, music, and space, is truly captivating. How did you develop this distinctive artistic language, and what influences shaped it?

I don’t really reflect on my style very much, to be honest. I think if you are an artist, you don’t constantly analyze what you do. You have to be driven by the process itself. You need to enter a certain flow in order to create something that works. If, at the same time, you are constantly reflecting on what you’re doing, it’s as if a second person is standing next to you, watching and questioning every step: What am I doing here? What am I doing there? I find that difficult, and that’s why it’s hard for me to describe my style. When I walk around or spend time somewhere, I’m always an artist—I’m not a private person who switches that off. I am who I am. I might notice a particular light while walking, discover an interesting piece of architecture, or see reflections on the surface of water—any kind of phenomenon in the world. That’s why I always carry a small camera with me. It’s a professional one, but compact enough to fit in my pocket. Whenever I encounter something that interests me—even if I don’t know why at that moment, or whether I’ll ever use it—I record it. I simply collect it. In that sense, I’m first and foremost a collector. I have a large archive of material: film and also photography. This archive is my pool. Everything goes into it, without knowing if or how it will ever be used. When I have a concrete project or an opportunity to show work, that’s when I start making decisions. I ask myself: what kind of space is it? Is it indoors or outdoors? Is it a white-cube exhibition space, a theater stage, an industrial site? Every space has its own atmosphere.

Here in Hildesheim, for example, I’m working in an outdoor situation on the street. It’s a small city, and the site is a parking lot near a school building—not abandoned, but poorly maintained. It’s an unattractive space that people use every day without really caring about how it looks. There are no trees, no flowers, no aesthetic attention—just a neglected public space. But that, too, is an atmosphere. When I encounter such a space, I try to spend time there and absorb its mood and feeling. I take notes, write down thoughts and associations—whatever comes to mind. When I begin working, I carry this atmosphere with me. Then I return to my archive and look for material that resonates with the specific situation. I decide whether to follow the space, to develop it further, or to work against it with my videos.

// So you mainly work by improvisation, right?

In the beginning it is, but the closer you get to the end, the more concrete and fixed they become, because one decision leads to the next. If you start with a slow movement, you might think, should I contrast it with something very hard? Or maybe you decide you don’t want that at all. Last month, I showed work in a church, and during the process it became absolutely clear that this is a space where people pray—whether I personally pray or not. People go there to pray, and I need to respect that. This is part of the atmosphere of the space, so I didn’t want to shock anyone or impose something aggressive. I thought about a person coming into a church and asked myself what kind of space might be meaningful for them. What kinds of thoughts could I introduce? Maybe I could gently extend or deepen their thoughts. As a result, the work had no hard cuts and no fast rhythms. It was very slow. It was also about beauty—though, in fact, all of my work is about beauty. Beauty is important.

// What role do you imagine the viewer playing within your installations, and how open are you to unexpected interpretations?

Of course, every artist wants success and wants people to like their work. Everyone is happy when people say, “That was interesting,” or “That was good.” But you can’t make work for the public. If you constantly think about who might come and what they might think, the work turns into a kind of city-marketing or video-design product—something that’s just meant to be nice. And even then, you can’t please everyone. There will always be people who say, “What is this? It’s just a waste of electricity,” or “I don’t like square forms—they’re too hard,” or “I don’t like the color blue; it’s too cold.” The next person will say, “I love blue—it reminds me of summer.” So you see, you can’t satisfy everyone. And it’s not the job of an artist to please people. The reason an artist works is to express something—because something has to come out—whether people like it or not. As I mentioned with the example of the church, of course I’m respectful of the context. If people come there to pray, I don’t want to disturb them. There’s no reason to do that. But beyond that, people will always find things they dislike:“I didn’t like this part,” or “That passage was too heavy for me.” If you try to take all of that into account, the work turns into a kind of confused soup. So I don’t work according to what people might think. Of course, I care—I enjoy compliments and I want people to like my work—but I can’t create work simply to please them.

// As I’ve noticed in your video installations, visitors cast shadows as they pass through them, creating the impression that they are meant to be drawn into the visual story. Is this something you plan or is it a spontaneous effect?

It’s not always like this, but when the situation is like this, it’s fine with me. Often there are technical reasons for it. It depends on where you can place the projector and how big your budget is. The more money you have, the more you can invest in high-end projectors and place them where there are no shadows, which can be very nice. Shadows can be disturbing, but that’s something I know in advance. So if I know there will be shadows—because the projectors can’t be placed elsewhere—then people simply become part of the image and the overall scene. And that’s perfectly fine with me.

// My last question for you: what advice would you give to young artists to help them find their own artistic voice?

First of all—and this is important—look at what others do. See how they deal with their subjects: sculptors, painters, and light artists. Don’t start at too low a level. Go to museums, visit major exhibitions, and really look. Do this consistently, sometimes over a long period of time. Try to understand why certain works are fascinating. How are they made? Why do they work so well? There are always reasons why a work succeeds and why it doesn’t. Try to learn from that and reflect on those reasons. That is one part. The other part is to forget everything I just said and start your own thing. Don’t look too much to the left or right, and don’t try to make work that looks like someone else’s—like James Turrell, for example. He is a personal hero of mine, and of course I wish I had had his ideas, because I find his work absolutely brilliant. But it’s already done. There’s no reason for me to become a second James Turrell. Instead, I have to ask myself why his work fascinates me so much. What is it that I truly like about it? And then I ask: how can I find my own way, through my own work, to develop something that is equally intense?

// It’s so inspiring! I am very grateful for the opportunity to talk to you today! Thank you so much!

FEATURED IMAGE

LICHTSTROM Ingolstadt 2021. Photo: Jennifer Braun.